– tl;dr –

When learning something new, pay attention at each moment to whether you’re studying a fundamental concept that requires deep mastery, or an emphemeral factoid. Optimize your study by doing whatever it takes to master the deep fundamentals, while just making sure to retain enough familiarity with the factoids to be able to find them again in the future.

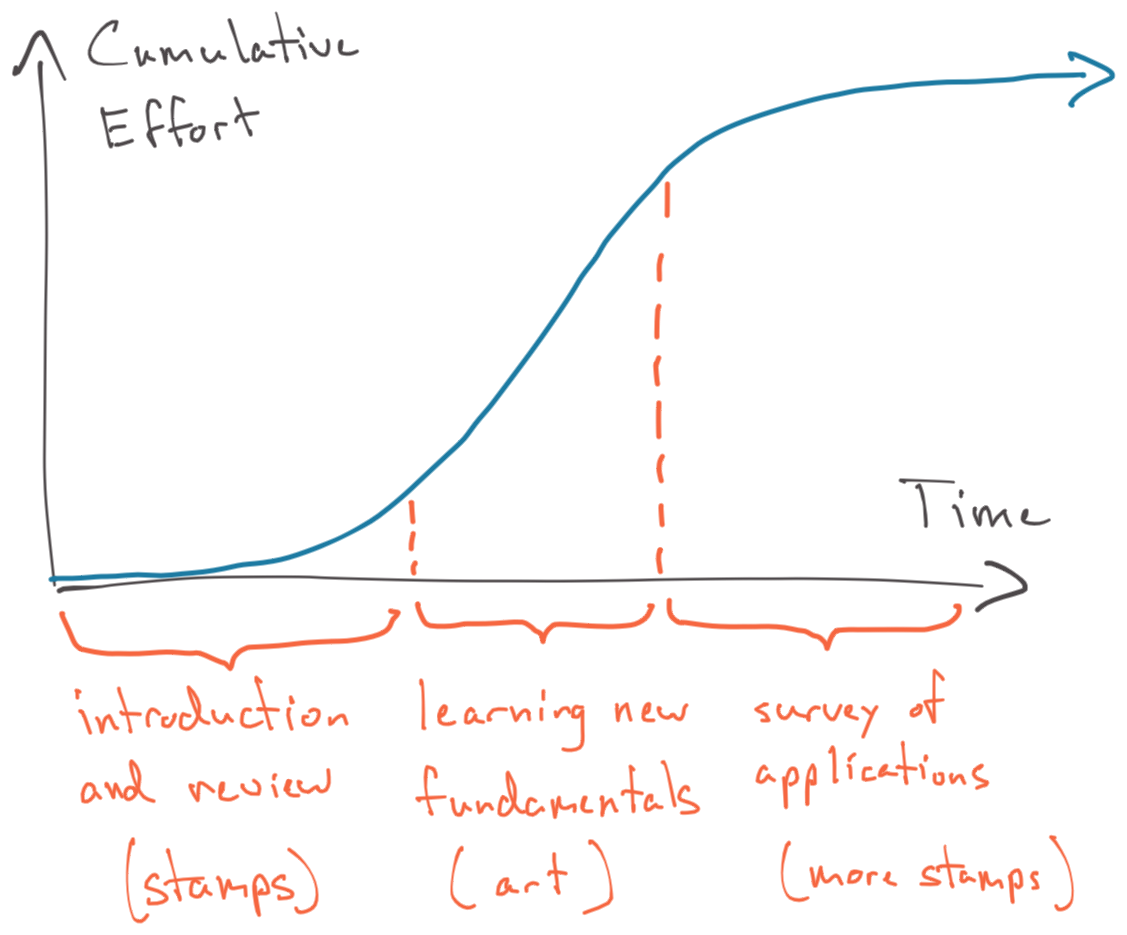

There are two different kinds of learning: stamp collecting, and developing an art. When you’re studying something new, it is useful to explicitly identify which of those phases you’re currently in, and to modify your approach to the study accordingly.

In particular, many STEM subjects follow a three part progression:

stamp collecting

↓

developing an art

↓

stamp collecting

For example, this happens all the time in engineering courses where the beginning of the course consists of an overview of topics you’re probably already familiar with; the middle of the course introduces new mathematical methods, formulae, or perspectives; and then the end of the course becomes a survey of how you might apply those new techniques to a variety of problems.

This structure is also why it’s very common in such courses for students to feel just fine with the class at the beginning; like they’re falling behind in the middle; and hopelessly lost at the end—all because they didn’t know how to appropriately recognize the phase of learning they were in, and adjust their effort accordingly.

When you’re stamp collecting, the important thing is to be aware of the existence of the “stamps” that are out there: after all, if you know they exist—and better yet, if you remember their names!—you can look look them up later, whenever you need them. For that reason, a good long-term outcome from a stamp collecting phase might merely be a passing familiarity with the existence of your stamps-in-question, and as a student you need not put so much effort into memorizing every particular detail of each individual stamp.

When developing an art, however, the scenario is flipped on its head. Instead of breadth, we have depth: you’re not tackling many things at a surface level, but just one or two things, deeply. Developing an art requires much greater effort because its rubric for a good outcome is much harsher: nothing less than mastery over a new technique. And attaining mastery here is essential to having a smooth follow-on stage of stamp collecting as you learn various applications of your new technique.

To make this solid, consider an introductory Calculus course:

At the beginning, you have a brief survey of the necessary algebra and trigonometry that you’ll need to employ. Stamps (because you’ve studied them before).

Then you dive into your first major, new topic. Let’s say it’s derivatives. All of a sudden you feel like you’re in the deep end of the pool, trying bravely to keep your head above the frothing water of h→0’s, infinitesimals, and tangent lines at points. This is what developing an art feels like, and it is essential at this point that you put in the extra effort to master these new techniques.

Finally, you step back to collect some more stamps: applications of derivatives in kinematics, in population growth rates, in identifying the maximum volume of boxes folded from single sheets of cardboard. If by this point you have truly mastered the art of derivatives, this is a piece of cake. If not, it’s a whirlwind nightmare. And the kicker? Once you’re done with the class, it may be quite some time before you need any particular one of those applications again—stamps in a drawer: remember their names so you can find them later, but everything else is bonus.

But the art of derivatives themselves? That will be a foundation for so many things to come.

The end result is that you end up with a sigmoid-like function for optimum study effort over time:

Expect it. Be on the lookout for when you’re about to enter a “deep study” phase, and ramp up your effort accordingly. Then you’ll be able to relax again when it comes time to collect more stamps.