I talk a lot about comparative advantage, and finding ways to trade on it. But one of the things I’ve never directly defended is the idea that strong comparative advantages can exist, and that you can improve your chances of developing such comparative advantages by studying more or less anything at all.

So, here’s a quantitative estimate.

Imagine forming a multi-dimensional vector representing your level of productivity on various tasks. Now, asking whether you are likely to have serious comparative advantages compared to someone else is akin to asking whether your productivity-vector points in a different direction to theirs. What are the odds of that happening, even in the worst case scenario, where your study is left to chance?

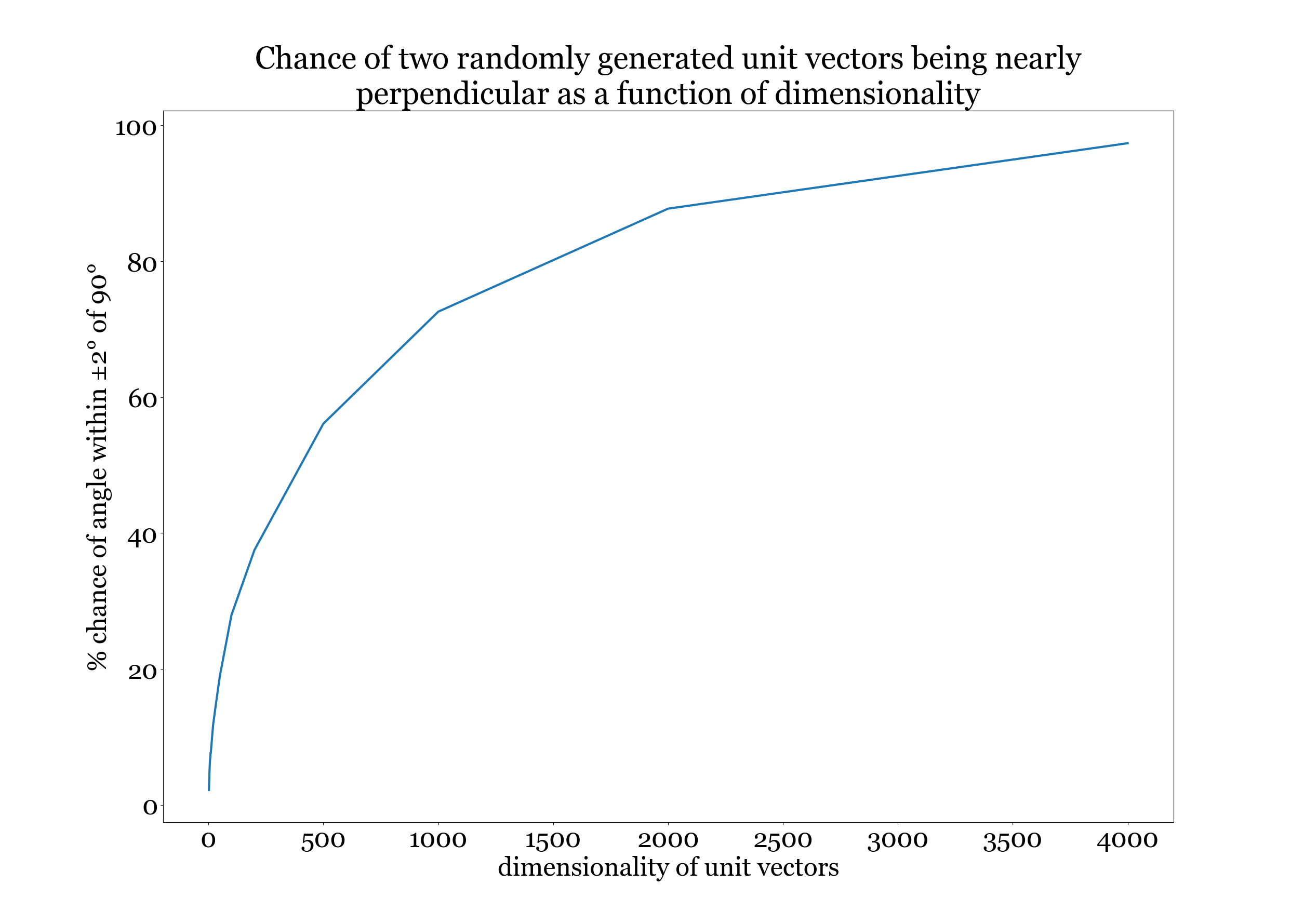

To get an idea of the numbers, we’ll pick some different dimensionalities, generate a bunch of random unit vectors of each dimensionality, and just look at the angle between the vectors of the same dimensionality. To make things even more concrete, we’ll pick a cutoff (in this case, ±2°) and ask “What is the chance of two randomly generated unit vectors of a given dimensionality being within ±2° of 90°?” This will tell us not only the chance of having a significant angle between the two vectors, but the chance of the two vectors being nearly maximally un-aligned. Or, in other words, the chance of really significant comparative advantages existing.

So there it is. Study things—almost anything at all, and the more the better—and you’ll be practically guaranteed to develop significant comparative advantages that you can use for mutually beneficial trade.